Social media has been one of the major drivers of the human response to COVID-19. It’s been encouraging to see that the dominant response—at least from my view—has been attempts to mobilize others to practice behaviours that have the best chance of flattening the curve.

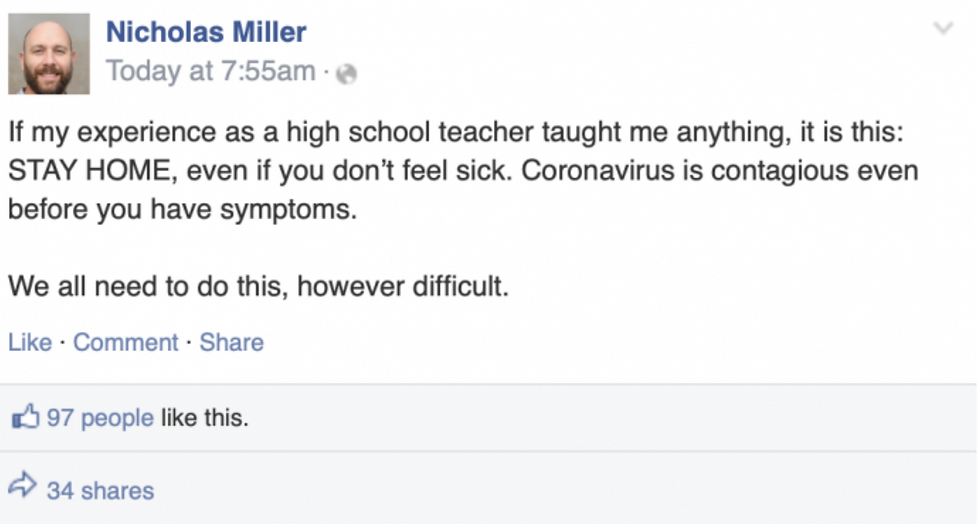

Various types of messages have proliferated. Some are informational and contain simple directions for what to do, like this one:

Other posts contain instructions for what to do but also include moral messages. For instance, instead of just saying “please share widely” at the bottom of the above message, it could be altered to say, “Be a good person—please share widely” or “It is your responsibility as a citizen to share this message widely.” Those two alternate versions of the text turn out to reflect two different kinds of moral pleas—deontological and virtue, respectively—a distinction that will become important below.

The key question is, does it matter whether a plea contains a moral justification for action and, if so, are some moral justifications more effective than others?

A team of researchers, led by Jim Everett at the University of Kent, has moved forward absurdly quickly with work on the effectiveness of the messages we send others about COVID-19. Keep in mind that this is super-fast paced—this research began a week before their work was released in a preprint on March 20. Of course, that means it’s not yet peer-reviewed (which is an important part of the publication process but takes time), so the findings need to be taken with caution. However, there are some key things to note that might tentatively inform social media communications.

Everett and colleagues were interested in whether some social media posts are more effective in altering intentions to take measures to reduce the spread of COVID-19 (e.g., social distancing, hand washing, & avoid social gatherings, send relevant messages on social media). They hypothesized that moral messages would be more effective than non-moral messages. They also posited that moral messages that cite responsibility/duty and virtue would be more effective than messages that were utilitarian (i.e., those that referenced consequences of non-action). Their full set of pre-registered hypotheses can be seen here.

They conducted an experiment to test these ideas, in which they gave different groups of people in their sample of 1032 US participants one of four versions of a Facebook message. All participants saw a fictitious post that said in the first paragraph, “STAY AT HOME, even if you don’t feel sick. Coronavirus is contagious even before you have symptoms.” For all participants, the post had a second paragraph. For some, the text was non-moral. It looked like this (all survey materials are found here):

Other participants were given one of three moral messages in that second bit of text:

Moral message 1. An appeal to consequences—any sacrifices we make now are small compared to if we all do nothing. The statement “THINK OF THE CONSEQUENCES” prominently completing the post.

Moral message 2. An appeal to virtue—you’re a good person if you behave this way (“BE A GOOD PERSON”).

Moral message 3. An appeal to duty—"it is our duty and responsibility to protect our families, friends, and fellow citizens”), with the statement “IT’S YOUR DUTY” prominently completing the post (this is considered a deontological argument—one in which right and wrong are based on particular rules).

What did the researchers find? While some support was garnered for the relative effectiveness of the duty and responsibility message, support was not found for the effectiveness of virtue message. In short, one form of moral message appears to be more effective than non-moral messages. According to the authors, the results suggest that messages focused on duty and responsibility towards the people around us and our fellow citizens are most effective in enhancing the behavioural changes necessary to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

That conclusion may be stating things a little too strongly—particularly because the research measured self-reported behavioural intent and not actual behaviour (which, of course, would be much harder) and because most of the hypothesized effects on intentions were not significant. One thing did, however, jump out out at me as possibly the most important finding: participants who saw the duty and responsibility post expressed significantly greater intention to share the message compared those who saw non-moral and virtue-based message. If that effect ends up being replicable, it’s an important finding—with greater sharing, more people will be exposed to the message, resulting in greater potential for behavioural change.

The jury is still out on whether that effect can be reproduced and it’s not yet clear why people might be more compelled to share duty and responsibility messages than other kinds of messages. There are other things to think about too. For instance, the further you get, culturally speaking, from the US population, the more likely it is that we'll see different effects of moral messaging, which is important to consider given that many of us have networks that span the globe. Further, I suspect that particular kinds of moral justifications will sound disingenuous coming from certain people (e.g., those we don't trust and those we don't expect to express such sentiments). Fortunately, according to Molly Crockett, one of the paper's co-authors at Yale, this research group will be continuing to investigate:

Again, take it with a bit of caution—it’s early work, but I found it interesting and worth sharing. Additionally, what I've reported is a small portion of what the authors investigated and found. I didn't, for example, discuss demographic differences or effects on second order beliefs (i.e., how participants believed other people, not themselves, would be affected by the posts). While effects on behavioural intent are what I took to be most interesting and valuable, you might find other things to consider in the full preprint, which can be found here.

コメント